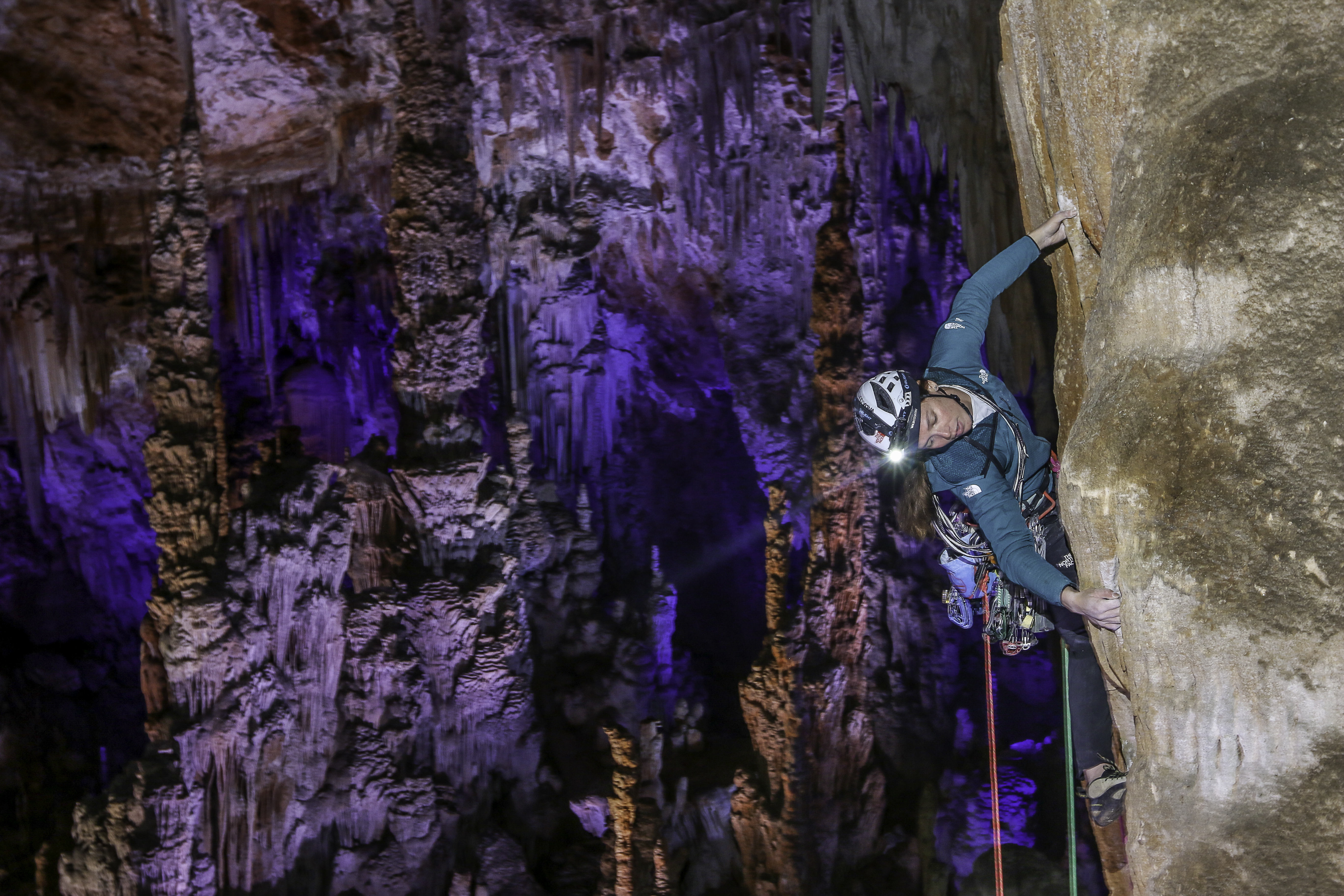

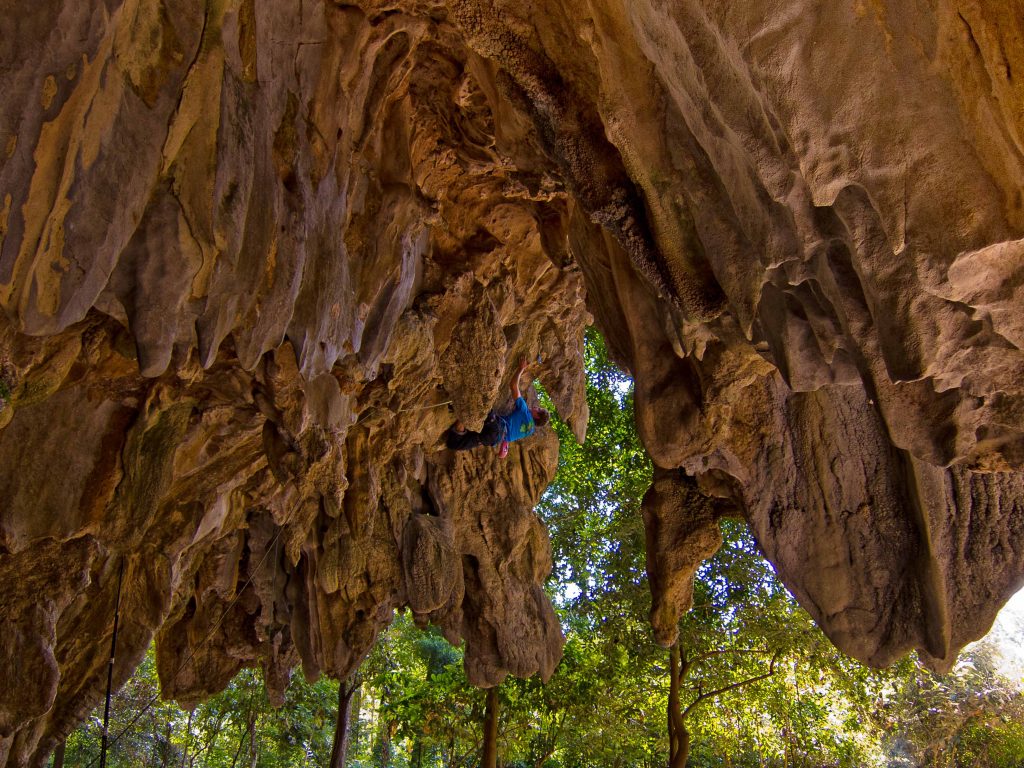

Trad climbing underground in “La Grotte de la Salamandre”

Pics are from Phil Bence/ The North Face

Text is from James

Thinking outside the box

This article seems to have raised a lot of comments, sometimes very negative, especially from the American caving community. We are sorry if we upset any of you, please keep in mind that we were mainly aiming to find ways to fuse the spirit of adventure AND carbon consumption decrease. Close to our home, there are hundreds of limestone caves. In many of the more accessible ones, climbers already climb and bolt, often on beautiful calcite formations. On an introductory day of caving, we realised that the cave system was a continuum of the terrain we are already familiar with on the surface, and began thinking about climbing underground. La Grotte de la Salamandre, an underground cave 50m under the surface with an aven (a natural opening in the roof of the cave) seemed quite a logical place to climb, even if this time we were entering the world of spéléologie. As James and I have no experience at caving at all, we asked for experts’ advices and were constantly under the supervision of 2 experienced French cavers, and always had the allowance of the “Grotte de la Salamandre” team management. If you want more explanations and details on how we did things, please read the bottom part of the article.

2021 is definitely a year of change that has further encouraged us – James and me – towards reducing our carbon footprint. At 35, traveling less is almost an easy choice when you’ve been moving as much as we have. Without even talking about ecology, after years of adventures between Japan, Africa, the USA, the desire would almost have arisen on its own… However like so many others, we do not quite want to stop everything, but rather to discover differently, more calmly, taking time for the little things. So traveling less far and for longer is an obvious answer to these questions. However, that does not mean the end of our adrenaline rush or our desire for adventure.

But how can you be surprised while climbing around your home? How to touch virgin rock that is worth the effort? Or to try something new when the smallest piece of rock in France, where climbing is a democratised sport, has already been cleaned up and planted with bolts?

In the past we’d have simply taken a plane ticket to a far away place in a random “developing” country, to go “hunting for virgin stone”. It was surprisingly easy to do and a lot of fun, but after almost 10 years of global expeditions, sometimes several times a year, but we started to wonder if there was not another way. Our ideas for more local projects started to form, and when Covid 19 came along and forced everyone to think very local, it seemed like the perfect time to put them into action.

At first we weren’t expecting much, and like so many of you out there we were after a little bit of freedom between the confinements, de-confinements and all the moments of uncertainty … The various travel restrictions fixed simple rules for us, which made choosing between our various ideas quite easy. We would stay close to home in our own department and every day we had to be back home by 6pm – that was it.

Seynes, Russan, La Capelle-et-Masmolène are the great classics less than 30 km from us. These venerable old ladies are still full of lines we haven’t put our fingers on, but for untouched rock without chalk, nor bolts, we’d have to have to look somewhere else.

* * *

Phil Bence is a caver of internation repute, and has been organizing the Ax-les-Thermes mountain film festival for many years in the south of France. Having invited us every year for the last 7 editions to present various of our movies, he’d also had time to introduce us to his underground world, and the beautiful rock formations that you can find underground. Climbing on steep tufas is one of my favourite styles of climbing, and I marvelled at how magical it would feel to be up there on what I can only describe as some of the most incredible tufas I had ever seen. The big problem obviously is that caves are wet and dirty! Everyone knows that!

Well not all of them apparently… Phill assured us that whilst “dry” caves are rarer than their soggy brothers, they do exist, and that suggested a cave almost under our house, the “Grotte de la Salamandre”. In the heart of the garrigue, located 26 km from our home, it seemed almost too good to be true, and when Phill sent us some photos from inside of the cave, we knew we had to go and take a look! La Grotte de la Salamandrew is a “show cave” open to the public, which basically means anybody can turn up and pay to take a guided tour of what must surely be one of the more impressive caves in the South of France. What made the cave even more special for us was that there is an actual Aven, a natural chimeney leading to a tiny hole in the roof that we hoped to be able to climb up and out of. Thanks to Pierre Bévengut, an other expert caver and the manager of the cave, and an open-minded and available team, we quickly obtained their support and permission to attempt the first climbing route in this gigantic 90m deep cave, following the obvious “dormouse route” from the floor, back to the surface. Each year, these small rodents descend underground, always following exactly the same route, along delicate tuffas to the cave floor. It seemed obvious to follow their example from the ground up, and as this was an environmentally concious project, we decided to do our best to climb the route with trad gear, without any bolts, so as not to leave any traces of our passage, other than our chalk.

From the ground everything looked like it would be quite easy, our head torches making strange shadows that gave the impression the rock was covered in big jugs. Unfortunately, once on the rock, things were a different matter, and from the 2nd meter of the route I realised that these little dormice climb as well as squirrels, much better than me! For the first time in my life, I had the chance to put my hands on truly perfect tuffas! White, often translucent draperies sparkling with calcite under my headlamp, formed over thousands of years, and fully protected from the assaults of the surface wind and rain. Such a privilege did it feel to be climbing down!

Placing protections between these formations was a new exercise, and whilst the placements were mostly good, I had no idea of the integrity of such rock, having never before climbed anything like that in my life. Often placing 3 Friends at the same hight between the fingers of 4 parallel draperies, hoping that somehow the expansion of all 3 might somehow equalise out, I quickly decided the best solution was simply not to fall, as much for protecting the stunning rock as my own safety.

If I wanted adventure, then I definitely had my fill of it, taking 2 hours to overcome my first 12 meters, pumped as hell and generally feeling very alone in the dark of the large silent room. For pitch 2 James took over, beginning with a very scary section on poor crumbly rock, that got better and better until an unlikely overhanging passage on giant hero jugs took him to a hanging belay on giant stalagmites in the middle of the wall.

Our last pitch, the last 20 meters towards the surface, was finally the most normal, climbing up and into the chimney of the Aven. Little by little we rediscovered the white limestone of our region we know so well, compact and cracked, easier to protect. Whilst the rock inside the cave was a little dirty and dusty in places, for virgin limestone that has never seen a stiff brush it was actually surprisingly good! It seems almost ironic that the conditions only became bad at the end of the final pitch, where the rock is at the mercy of the elements, and the mud and leaves it might wash within. After an unexpected battle a few meters from the end, I made it, joined eventually by James atop this incredible hole in the earth!

It was fitting that Phil Bence, with his great habit of caving photos was there with us to capture this rather strange and different route, and even working with him on the photos showed us that there is always something new to learn! This was our second local adventure in the space of a year, and not only proof that there really are new things to be discovered right here on our doorstep, but also an interesting new balance of “expedition life”. Leaving home in the morning, we found ourselves soon thrown into the same new emotions that we usually find whenclimbing on the other side of the world, yet by 5pm each day it was time to clean up dust ourselves down, head back and collect our 2 year old son from his nanny, and slip just as quickly back into our typical evening routine in the comfort of our own home!

A few extra informations for the curious:

1) The project was a joint idea between ourselves and Phil Bence, a world renowned caver and explorer with close to 30 years of experience in the underground world. Phill grew up caving in the South of France, and has made caving expeditions to most corners of the earth. He has personally discovered and opened 10’s of KM of cave systems.

2) The project was carried out in a private cave, La Grotte de la Salamandre, under the supervision of Pierre Bevengut, an other very experienced caver and at all times we climbed under their supervision. We had the special allowance of the Cave’s management team. La Grotte de la Salamendre is a “ show” cave in the south of France, and is visited each year by thousands of tourists. To make the cave accessible to the general public, concrete walk ways and metal barriers were installed to guide people in and around the cave, as well as a 30m long security tunnel blasted to facilitate access to the site. Whilst I can’t deny that our presence in the cave didn’t have an impact (anybody, doing anything has an impact on their environment, it’s the simple fact of being alive), our “impact” was certainly minimal in comparison to this.

3) We climbed directly underneath the “Aven” (a natural opening in the roof of the cave) as it made most sense for us, as climbers, to be able to climb up and out of the cave, back to the “real” world above. The rock under this opening, as can be seen in the attached photo, is mostly open to the elements, and so the Speleothem formations, whilst impressive, are small in comparison to those in deeper parts of the cave, and similar to what we find on some overhanging limestone crags. I can understand that if people haven’t read the full text or looked at the complete gallery of photos, they might assume we also climbed on the incredibly delicate formations sometimes seen in the background. This was not the case.4) We chose to climb the route using traditional climbing equipment and techniques. Effectively this means we removed all of the protection we placed during the climb, and didn’t resort to drilling holes to place bolts, a very common practice in caving. Again, whilst we can’t say our passage left no trace (we cleaned some mud off holds, and used chalk) in comparison to “typical” caving techniques used to access new areas of a cave system (bolting anchors, aid climbing, even blasting with explosives) we believe it was very minimal. We were the first people ever to visit that part of the cave, and inspected some passages visible, but not accessible from an abseil rope to see if the network continued.

5) As far as I can tell (better to confirm with a geologist?) The calcium carbonate Speleothems you find in caves are the same as those found on overhanging limestone, with the main difference being that due to the lack of light in a cave, there is minimal or no microscopic plant life growing on the surface that gives “normal” Tufa its colours. Climbers climb on Tufa all the time, all around the world, and it doesn’t cause a problem.

American climbers have raised the issue of touching calcium carbonates, as they say that it disrupts the formation process. The advices we took in France didn’t mention anything about not touching them. According to our cave contacts, in France this topic isn’t really an issue and doesn’t seem to have a consensus. When they explore a new cave they do touch the formations as well when they find their path and climb to access a new area. It seems to be rather a difference of ethics between different places. Just like in climbing, ethics say that it’s ok to bolt in most areas, but totally off in the Peak district for exemple.

Alternative version of text:

Clearly this advice doesn’t align with everyone, especially with regards to touching calcite formations, and again if this has upset people we can only apologise. Differences of opinions are nothing new, and can often be explosive on topics close to our hearts. But be they political, social, or anything in between, I like to think that they offer an opportunity for us to learn and to grow.

In a domain where we feel more competent, climbing is also full of ethical discussions and dilemmas. Depending on where you come from, and how you began your journey into the sport, your approach and view of what is acceptable may differ wildly from ours. As an example, the placement of bolts for protection is widely accepted in mainland Europe, yet completely outlawed in the majority crags in the UK. The Czech Republic, the country often seen as the bastion of strong climbing ethics, where even the use of chalk is banned in certain areas and protection for traditional climbing relies on knotted slings, still allow the use of certain types of bolts, in certain places, as long as they follow certain rules. In the USA, bolts are commonplace on trad routes, as well as big walls throughout the country, but in many areas they can only be placed using a hand drill, not a power-drill.

The rules we play by are made up by us, and are often based on little more than how we’ve done things before. Is there such thing as a “right” and a “wrong”, a “good” and a “bad”. Perhaps all we can hope for is to discuss the ideas that seem important to us and remain civil and courteous along the way.

We followed advice from experts in the field, and believed to be acting in a responsible way, yet we’re not so arrogant as to say we know best. Ecology and environmental impact are important topics for us, in all aspects of our lives, and we will continue to keep on searching for adventure, asking questions and hopefully getting wiser along the way.

After listening to peoples opinion, we want to underline that the underground world is a fragile one and every choice has to be educated. What we hope to make people remember, is that Adventure IS possible next to home, and that we don’t need to fly 10 000 km every time to experience it!

James and I do care a lot about the environnement, our projects are more and more impacted by this topic (see our Bike and climb recent trip), we offset all of our carbon expenses since 5 years with Mossy Earth.